It is a sad fact that civic art is often also pretty crappy art. This is partially due to who commissions it; an artist making a statue to appease a committee and not offend a populace is unlikely to make bold or striking choices, and said committee, when choosing from a slate of possibilities, is equally unlikely to settle upon a work that could unsettle their constituents. Civic art is nearly always safe art, and safe is one of the more damning adjectives in the art world. But civic art, especially statues honoring individual citizens, has a purpose beyond and before artistic merit. It carries a message; there is a moral to its story. There are times when the story a statue is meant to tell will by necessity limit its artistic statement, and that’s not always a bad thing.

Bill Russell is getting his statue, and it only took a magazine article and a Presidential Medal of Freedom to get Boston around to it. Rob Peterson makes the case over at Hardwood Paroxysm that the statue should be something other than the run-of-the-mill representation of a man in some artistic pose. His suggestion is Russell’s hands, rising from the earth to grasp a basketball, a sort of extension of the idea embodied in the statue of Joe Louis’s arm in Detroit.

But to honor Bill Russell with a statue of hands holding a ball is to miss half of why Bill Russell deserves a statue. Russell’s story, as Peterson makes clear, is a story of athletic glory. Wherever he went, no matter what his personal box score read, Bill Russell and his teams won: 2 NCAA Championships, 11 NBA Championships. He won 5 MVPs even though Wilt Chamberlain put up cartoonish numbers during many of the same seasons. His athletic, ball-hawking defense quite genuinely changed the way high-level basketball was played. It’s hard for those of us who weren’t alive at the time to appreciate exactly how good he was, and the grainy highlights reels of him in action, while giving glimpses of his dominance, also show just how much the game has changed since then without driving home the fact that he was perhaps the most important catalyst for that change. He is the Babe Ruth of the NBA, a living legend whose dominance defies belief. He has more rings than fingers! A hand’s worth more than MJ, current consensus GOAT! On athletic merits alone, Bill Russell deserves to have been given his statue decades ago, and Peterson’s idea of hands snaring a ball would be a fine way to commemorate that career.

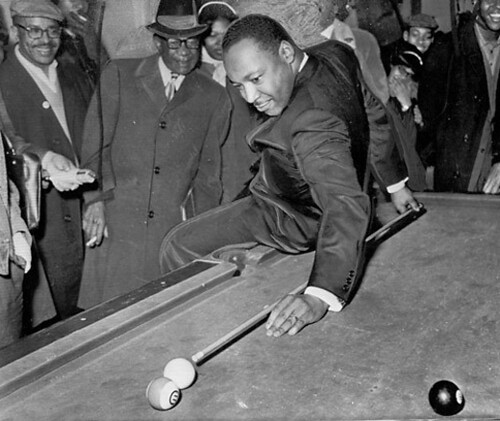

But such a statue would do a disservice to Bill Russell the man. The video embedded at the top of the Globe article announcing the statue was split into two parts for a reason, with the second being dedicated to Russell the Activist. Bill Russell used his fame as a pulpit. He was a proud man, unflinching and willing to ruffle whatever feathers he had to to prove the point that he was equal to any other. He marched with King. He refused to play games in cities where the black Celtics weren’t served in restaurants. He won over the city of Boston, but he lives on an island in Seattle because he couldn’t live in a city he knew was racist. Bill Russell lived in an America that was often openly racist, and he made a point to not back down from that racism. They don’t give you the Presidential Medal of Freedom for winning NBA Championships.

Ta-Nehisi Coates wrote an article recently about how the birther media trial of Obama’s citizenship is part of a long tradition of attacks on black citizenship, and how important it is for the America that is so often excluded from portrayal to be manifested publicly. Because the past is a racist (and sexist) place, as well as because erecting statues to honor our civic heroes largely died off during the 20th century, virtually all statues in Boston (and elsewhere) commemorating people commemorate white men. Joe Louis’s fist is pointed South to signify his fight against Jim Crow laws, a symbolic alignment appropriate for a man whose very celebrity was a blow to racism. Joe Louis wasn’t a mouthpiece of civil rights because he couldn’t be. In his time, being an African-American athlete portrayed as a gentleman was transgressive enough. Aligning the fist towards the South is an elegant acknowledgment of that import.

“I hope that one day, in the streets of Boston, children will look up at a statue built not only to Bill Russell the player, but Bill Russell the man.”

-Barry Obama

But Bill Russell used his position on the shoulders of athletes like Joe Louis to further their cause. He spent his adult life advocating for equality, loudly and publicly. He deserves a statue at least as much for that as for his eleven rings. It’s not a surprise that Beverly Morgan-Welch, of the Museum of African-American History, wants the statue to be of Bill Russell in a suit. She would ignore Bill Russell the player, but not for no reason. The best suggestion in the video is actually Tommy Heinsohn’s: the idea is as clumsy as the digital rendering, but his is the only suggestion that tries to encompass both parts of Russell’s greatness. To erect a statue for Bill Russell that didn’t show his proud black face would be a mistake and an insult. While a statue of Joe Louis’s fist is an elegant work of artistic metonymy because Louis broke barriers simply through proud achievement, Bill Russell fought to be acknowledged as a man, not just an athlete, and a statue of him must acknowledge that truth. To show his hands grabbing a ball would be to celebrate his glory on the hardwood, but to simultaneously deny his importance out of sneakers. It may be artistically clumsy, even hokey, for Boston’s statue of Bill Russell to be his whole body rather than just his hands, but the point of the statue is not really to be great art. It is not Bill Russell’s hands that deserve a statue, it is his brain and his heart. Any statue that fails to show that is the wrong statue.

No comments:

Post a Comment